Happy Birthday Wikipedia!

Read more about Wikipedia’s 25 year history, covering its early days with a ‘then and now'(and what lies ahead), at the link below:

At 25 years old it may be the olddddd man of the old Internet but Wikipedia still remains the largest reference work on the Internet and is now a chief training dataset for pretty much all the major Artificial Intelligence answer services you may encounter every day while also still remaining a place where such universal and lofty ideals persist such as: writing with a neutral point of view; citing what you write; the reliability of sources; the verifiability and accessibility of sources; objectivity; writing for a lay audience; avoiding bias; avoiding political interference and conflict of interest; navigating copyright and open access; use of academic referencing and more.

All of these aspects transparently debated and worked at day after day as we all know neutrality is something that can never be assumed and always has to be worked at. And where information can always be checked, challenged and corrected. Some pages we know are highly scrutinised (and padlocked) so that an experienced editor has to check any new addition is sufficiently and responsibly referenced (re: Donald Trump, Obama, Israel v Palestine conflict pages etc). Other pages are perhaps less well visited, and maybe just newly written (e.g. the Conan Pictish Stone), so may need that extra care and attention to ensure the content is expanded, copyedited and honed to perfection. An information literate user of Wikipedia will see that… but shouldn’t we all be, or try to be, more information literate when it comes to viewing content on the web? At least contributing to Wikipedia both helps the information readily available online AND the contributor to be that bit more information literate and vigilant about questionable material elsewhere online.

Volunteers (and automated bots for some of the more mundane tasks like date formatting, citation formatting and vandalism removal) help scrutinise, copyedit and revert content all the time based on what the reliable published secondary sources outside of Wikipedia tell us. Sources that we rely on. In this way, by adhering to community agreed procedures on best practice developed over the last twenty-five years and the need for always backing up what you write through citing reliable sources, the work of volunteers is all about attaining a measure of trust, of consistency and of determining where a consensus can be arrived at… all so that a holistic topic overview be provided on any given subject that our readers can rightly hope for and expect.

That’s unpaid labour, volunteers giving of their time, passion and expertise and, 25 years on, it really ought to be better understood and appreciated in these terms. AI represents a shift undoubtedly but the need for a free, ethical, open knowledge hub for the world remains (and especially with that human element as its ‘special sauce’) as it also needs to be ever growing and ever updating to feed these often parasitic GenAI services who are beginning to realise they need to support where the large amounts of free knowledge they consume voraciously actually comes from. And that they themselves will come to rely on when they need access to new and updated pages to train their AIs on if the information they provide is not to become badly out-of-date or degraded.

When you turn on a tap you expect clean water to come out. When you search online you (ought to) expect good verifiable factual information to be returned.

Though not 100% perfect (where on the Internet is?) there is much to admire about Wikipedia volunteers caring enough about a topic to share it openly and surface it to where the world can learn all about it for free.

And facts matter. Or at least they ought to, shouldn’t they?

Cite what you write, write neutrally, write in your own words. These are the core tenets of Wikipedia. And each volunteer contributes with those principles at the forefront of their mind.

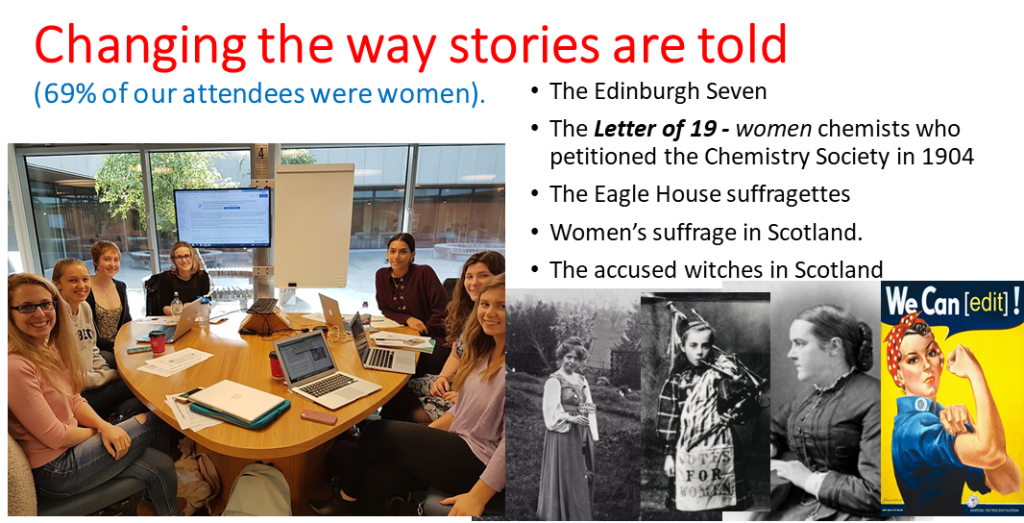

Bad actors may (and do) persist in the world outside of Wikipedia, trying to muddy the water and the health of our information ecosystem; in social media terms, news media, politics and more. But the positivity Wikipedia engenders, and the impact and agency of contributing to Wikipedia, is felt by our students at the University Of Edinburgh and helps contribute to their graduate competencies and professional development.

Rosie Taylor and Isobel Cordrey from the student support group, Wellcomm Kings, co-hosted the LGBTQ+ History month and Global Alumni event.

Our students firmly believe, and take pride in, the societal good of Wikimedia’s mission to share factchecked knowledge around the world for the benefit of all. That optimism, redolent of the early days of the internet, is something that persists just as much now as any bad actors trying to now game the system. It’s just about which wolf you feed and choosing what you value: illuminating the world with knowledge, building understanding, democratising access to information.

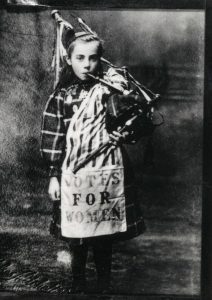

Whether it is about Scottish suffragettes, Edinburgh’s Royal Mile and its alleyways like ‘Fleshmarket Close’, or the individual accused witches’ histories from all around Scotland, or Pictish stones, or Hebridean storytellers and singers, Gaelic poets, the Burns Supper and its once hideous pictures of haggis (now much improved thankfully) and much much more…. our students have been helping to tell the history, culture, geography and tales of the people of Scotland online and making use of the vast treasure-trove of knowledge in the sometimes forgotten or overlooked non-digitised world (books, textbooks, news articles, journal articles, newspaper archives etc).

(Burns’ Supper image from public figure Evelyn Hollow added to Wikipedia on Burns Night 2024, Stinglehammer, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

And as an international outward-looking and knowledge-generating institution, the University of Edinburgh also is ‘walking the walk‘ in demonstrating its commitment to sharing knowledge openly outside ‘the ivory tower’ of academia and its knowledge silos through contributing to Wikipedia as a form of ‘knowledge activism’. As our vision states, “Our graduates, and the knowledge we discover with our partners, make the world a better place.”

Not just sharing about Scotland’s histories I hasten to add and not just in the English language either but about ALL the topics, languages and cultures its students and staff are researching in and care about; whether on the people of Singapore; or art and artefacts of the Congo; Latin American literature; South African feminist writers; the history of Borneo; the Qingtian diaspora; Japanese fashion (historic and contemporary); LLMs; floods in Afghanistan; the history of menstruation; Francophone literature; Greek poetry; Neuroscience; heatwaves; earthquakes; reproductive medicine topics; volcanic eruptions; Korean culture and society; Black history; LGBTQ+ history; Gender history and much much more besides.

So here’s to Wikipedia, to free knowledge, and to caring about, and caring for, a healthy ethical information ecosystem that is accessible to all and works for all.

You can read about Wikipedia’s approach in being more nimble about its role in the information ecosystem in making deals with prominent artificial intelligence companies, including Amazon, Meta Platforms, Perplexity, Microsoft, and France’s Mistral AI.

And you can also listen to Wikimedia UK’s Lucy Crompton-Reid appearing on the BBC Radio Scotland morning show for five minute chat about Wikipedia’s birthday on BBC Sounds at 2:53:30 mark.

All good light-hearted banter about Wikipedia and how it ensures accuracy in today’s age (how does BBC for that matter, one could argue?) until sports presenter Phil Goodlad jokes that Martin Geissler’s Wikipedia page states erroneously that he is a Hibernian FC supporter and likes cats. It doesn’t. I checked. It correctly states he is a Hearts FC supporter and no mention of cats. So another £5 billion defamation suit seems in order! 🙂

ps. That Trump v BBC lawsuit is chilling though so best not joke about such things. In all honesty, I do think such lightweight jokey bants in a serious news show feed into the ‘Wikipedia is rubbish and easily vandalised’ trope which Lucy refuted in the piece and is thoroughly ‘old hat’ these days and 25 year ‘old hat’ at that.

But would settle for a mea culpa from Geissler & co. and/or £5 donation to Wikipedia. Definitely, presenter Laura MacIver ought to have a Wikipedia page if nothing else.