CC BY 2.0-licensed photo by CEA+ | Artist: Nam June Paik, “Electronic Superhighway. Continental US, Alaska & Hawaii” (1995).

Woodward and Bernstein, the eminent investigative journalists involved in uncovering the Watergate Scandal, just felt compelled to assert that the media were not ‘fake news’ at a White House Correspondents Dinner the US President failed to attend. In the same week, Jimmy Wales, co-founder of Wikipedia, felt compelled to create a new site, WikiTribune, to combat fake news.

This is where we are this International Worker’s Day where the most vital work one can undertake seems to be keeping oneself accurately informed.

“We live in the information age and the aphorism ‘one who possess information possesses the world’ of course reflects the present-day reality.” – (Vladimir Putin in Interfax, 2016).

Sifting fact from fake news

In the run up to the Scottish council elections, French presidential elections and a ‘strong and stable‘ UK General Election, what are we to make of the ‘post-truth’ landscape we supposedly now inhabit; where the traditional mass media appears to be distrusted and waning in its influence over the public sphere (Tufeckzi in Viner, 2016) while the secret algorithms’ of search engines & social media giants dominate instead?

The new virtual agora (Silverstone in Weichert, 2016) of the internet creates new opportunities for democratic citizen journalism but also has been shown to create chaotic ‘troll’ culture & maelstroms of information overload. Therefore, the new ‘virtual generation’ inhabiting this ‘post-fact’ world must attempt to navigate fake content, sponsored content and content filtered to match their evolving digital identity to somehow arrive safely at a common truth. Should we be worried what this all means in ‘the information age’?

Information Literacy in the Information Age

“Facebook defines who we are, Amazon defines what we want

and Google defines what we think.”

(Broeder, 2016)

The information age is defined as “the shift from traditional industry that the Industrial Revolution brought through industrialization, to an economy based on computerization or digital revolution” (Toffler in Korjus, 2016). There are now 3 billion internet users on our planet, well over a third of humanity (Graham et al, 2015). Global IP traffic is estimated to treble over the next 5 years (Chaudhry, 2016) and a hundredfold for the period 2005 to 2020 overall. This internet age still wrestles with both geographically & demographically uneven coverage while usage in no way equates to users being able to safely navigate, or indeed, to critically evaluate the information they are presented with via its gatekeepers (Facebook, Google, Yahoo, Microsoft et al). Tambini (2016) defines these aforementioned digital intermediaries as “software-based institutions that have the potential to influence the flow of online information between providers (publishers) and consumers”. So exactly how conversant are we with the nature of their relationship with these intermediaries & the role they play in the networks that shape our everyday lives?

Digital intermediaries

“Digital intermediaries such as Google and Facebook are seen as the new powerbrokers in online news, controlling access to consumers and with the potential even to suppress and target messages to individuals.” (Tambini, 2016)

Facebook’s CEO Mark Zuckerberg may downplay Facebook’s role as “arbiters of truth” (Seethaman, 2016) in much the same way that Google downplay their role as controllers of the library “card catalogue” (Walker in Toobin, 2015) but both represent the pre-eminent gatekeepers in the information age. 62% of Americans get their news from social media (Mint, 2016) with 44% getting their news from Facebook. In addition, a not insubstantial two million voters were encouraged to register to vote by Facebook, while Facebook’s own 2012 study concluded that it “directly influenced political self-expression, information seeking and real-world voting behaviour of millions of people.” (Seethaman, 2016)

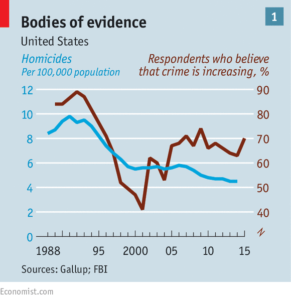

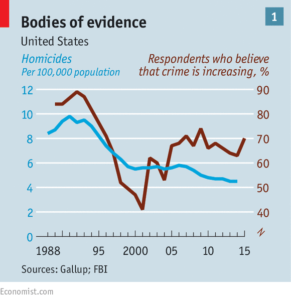

Figure 1 Bodies of Evidence (The Economist, 2016)

Figure 1 Bodies of Evidence (The Economist, 2016)

This year has seen assertion after assertion made which bear, upon closer examination by fact-checking organisations such as PolitiFact (see Figure 1 above) absolutely no basis in truth. For the virtual generation, the traditional mass media has come to be treated on a par with new, more egalitarian, social media with little differentiation in how Google lists these results. Clickbait journalism has become the order of the day (Viner, 2016); where outlandish claims can be given a platform as long as they are prefixed with “It is claimed that…”

“Now no one even tries proving ‘the truth’. You can just say anything. Create realities.” (Pomerantzev in the Economist, 2016)

The problem of ascertaining truth in the information age can be attributed to three main factors:

- The controversial line “people in this country have had enough of experts” (Gove in Viner, 2016) during the EU referendum demonstrated there has been a fundamental eroding of trust in, & undermining of, the institutions & ‘expert’ opinions previously looked up to as subject authorities. “We’ve basically eliminated any of the referees, the gatekeepers…There is nobody: you can’t go to anybody and say: ‘Look, here are the facts’” (Sykes in the Economist, 2016)

- The proliferation of social media ‘filter bubbles’ which group like-minded users together & filter content to them accordingly to their ‘likes’. In this way, users can become isolated from viewpoints opposite to their own (Duggan, 2016) and fringe stories can survive longer despite being comprehensively debunked elsewhere. In this way, any contrary view tends to be either filtered out or met with disbelief through what has been termed ‘the backfire effect’ (The Economist, 2016).

- The New York Times calls this current era an ‘era of data but no facts’ (Clarke, 2016). Data is certainly abundant; 90% of the world’s data was generated in the last two years (Tuffley, 2016). Yet, it has never been more difficult to find ‘truth in the numbers’ (Clarke, 2016) with over 60 trillion pages (Fichter and Wisniewski, 2014) to navigate and terabytes of unstructured data to (mis)interpret.

The way forward

“We need to increase the reputational consequences and change the incentives for making false statements… right now, it pays to be outrageous, but not to be truthful.”

(Nyhan in the Economist, 2016)

Original image by Doug Coulter, The White House (The White House on Facebook) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. Modified by me.

Since the US election, and President Trump’s continuing assault on the ‘dishonest media’, the need for information to be verified has been articulated as never before with current debates raging on just how large a role Russia, Facebook & fake news played during the US election. Indeed, the inscrutable ‘black boxes’ of Google & Facebook’s algorithms constitute a real dilemma for educators & information professionals.

Reappraising information & media literacy education

The European Commission, the French Conseil d’Etat and the UK Government are all re-examining the role of ‘digital intermediaries’; with OfCom being asked by the UK government to prepare a new framework for assessing the intermediaries’ news distribution & setting regulatory parameters of ‘public expectation’ in place (Tambini, 2016). Yet, Cohen (2016) asserts that there is a need for greater transparency of the algorithms being used in order to provide better oversight of the digital intermediaries. Further, that the current lack of public domain data available in order to assess the editorial control of these digital intermediaries means that until the regulatory environment is strengthened so as to require these ‘behemoths’ (Tambini, 2016) to disclose this data, this pattern of power & influence is likely to remain unchecked.

Somewhere along the line, media literacy does appear to have backfired; our students were told that Google was trustworthy and Wikipedia was not (Boyd, 2016). The question is how clicking on those top five Google results instead of critically engaging with the holistic overview & reliable sources Wikipedia offers is working out?

A lack of privacy combined with a lack of transparency

Further, privacy seems to be the one truly significant casualty of the information age. Broeder (2016) suggests that, as governments focus increasingly on secrecy, at the same time the individual finds it increasingly difficult to retain any notions of privacy. This creates a ‘transparency paradox’ often resulting in a deep suspicion of governments’ having something to hide while the individual is left vulnerable to increasingly invasive legislation such as the UK’s new Investigatory Powers Act – “the most extreme surveillance in the history of Western democracy.” (Snowden in Ashok, 2016). This would be bad enough if their public & private data weren’t already being shared as a “tradeable commodity” (Tuffley, 2016) with companies like Google and Apple, “the feudal overlords of the information society” (Broeder, 2016) and countless other organisations.

The Data Protection Act (1998), Freedom of Information Act (2000) and the Human Rights Act (1998) should give the beleaguered individual succour but FOI requests can be denied if there is a ‘good reason’ to do so, particularly if it conflicts with the Official Secrets Act (1989), and the current government’s stance on the Human Rights Act does not bode well for its long-term survival. The virtual generation will also now all have a digital footprint; a great deal of which can been mined by government & other agencies without our knowing about it or consenting to it. The issue therefore is that a line must be drawn as to our public lives and our private lives. However, this line is increasingly unclear because our use of digital intermediaries blurs this line. In this area, we do have legitimate cause to worry.

The need for a digital code of ethics

- “Before I do something with this technology, I ask myself, would it be alright if everyone did it?

- Is this going to harm or dehumanise anyone, even people I don’t know and will never meet?

- Do I have the informed consent of those who will be affected?” (Tuffley, 2016)

Educating citizens as to the merits of a digital code of ethics like the one above is one thing, and there are success stories in this regard through initiatives such as StaySafeOnline.org but a joined-up approach marrying up librarians, educators and instructional technologists to teach students (& adults) information & digital literacy seems to be reaping rewards according to Wine (2016). While recent initiatives exemplifying the relevance & need for information professionals assisting with political literacy during the Scottish referendum (Smith, 2016) have found further expression in other counterparts (Abram, 2016).

”This challenge is not just for school librarians to prepare the next generation to be informed but for all librarians to assist the whole population.” (Abram, 2016)

Trump’s administration may or may not be in ‘chaos’ but recent acts have exposed worrying trends. Trends which reveal an eroding of trust: in the opinions of experts; in the ‘dishonest’ media; in factual evidence; and in the rule of law. Issues at the heart of the information age have been exposed: there exists a glut of information & a sea of data to navigate with little formalised guidance as to how to find our way through it. For the beleaguered individual, this glut makes it near impossible to find ‘truth in the numbers’ while equating one online news source to be just as valid as another, regardless of its credibility, only exacerbates the problem. All this, combined with an increasing lack of privacy and an increasing lack of transparency, makes for a potent combination.

There is a place of refuge you can go, however. A place where facts, not ‘alternate facts’, but actual verifiable facts, are venerated. A place that holds as its central tenets, principles of verifiability, neutral point of view, and transparency above all else. A place where every edit made to a page is recorded, for the life of that page, so you can see what change was made, when & by whom. How many other sites give you that level of transparency where you can check, challenge & correct the information presented if it does hold to the principles of verifiability?

Now consider that this site is the world’s number one information site; visited by 500 million visitors a month and considered, by British people, to be more trustworthy than the BBC, ITV, the Guardian, the Times, the Telegraph according to a 2014 Yougov survey.

While Wikipedia is the fifth most popular website in the world, the other internet giants in the top ten cannot compete with it for transparency; an implicit promise of trust with its users. Some 200+ factors go into constructing how Google’s algorithm determines the top ten results for a search term yet we have no inkling what those factors are or how those all-important top ten search results are arrived at. Contrast this opacity, and Facebook’s for that matter, with Wikimedia’s own (albeit abortive) proposal for a Knowledge Engine (Sentance, 2016); envisaged as the world’s first transparent non-commercial search engine and consider what that transparency might have meant for the virtual generation being able to trust the information they are presented with.

Wikidata (Wikimedia’s digital repository of free, openly-licensed structured data) represents another bright hope. It is already used to power, though not exclusively, many of the answers in Google’s Knowledge Graph without ever being attributed as such.

Wikidata is a free linked database of knowledge that can be read and edited by both humans and machines. It acts as central storage for the structured data of its Wikimedia sister projects including Wikipedia, Wikivoyage, Wikisource, and others. The mission behind Wikidata is clear: if ‘to Google’ has come to stand in for ‘to search’ and “search is the way we now live” (Darnton in Hillis, Petit & Jarrett, 2013, p.5) then ‘to Wikidata’ is ‘to check the digital provenance’. And checking the digital provenance of assertions is pivotal to our suddenly bewildered democracy.

While fact-checking websites exist & more are springing up all the time, Wikipedia is already firmly established as the place where students and staff conduct pre-research on a topic; “to gain context on a topic, to orient themselves, students start with Wikipedia…. In this unique role, it therefore serves as an ideal bridge between the validated and unvalidated Web.” (Grathwohl, 2011)

Therefore, it is vitally important that Wikipedia’s users know how knowledge is constructed & curated and the difference between fact-checked accurate information from reliable sources and information that plainly isn’t.

“Knowledge creates understanding – understanding is sorely lacking in today’s world. Behind every article on Wikipedia is a Talk page is a public forum where editors hash it out; from citations, notability to truth.” (Katherine Maher, Executive Director of the Wikimedia Foundation, December 2016)

The advent of fake news means that people need somewhere they can turn to where the information is accurate, reliable and trustworthy. Wikipedia editors have been evaluating the validity and reliability of sources and removing those facts not attributed to a reliable published source for years. Therefore engaging staff and students in Wikipedia assignments embeds source evaluation as a core component of the assignment. Recent research by Harvard Business School has also shown that the process of editing Wikipedia has a profound impact on those that participate in it; whereby editors that become involved in the discourse of an article’s creation with a particular slanted viewpoint or bias actually become more moderate over time. This means editing Wikipedia actually de-radicalises its editors as they seek to work towards a common truth. Would that were true of other much more partisan sectors of the internet.

Further, popular articles and breaking news stories are often covered on Wikipedia extremely thoroughly where the focus of many eyes make light work in the construction of detailed, properly cited, accurate articles. And that might just be the best weapon to combat fake news; while one news source in isolation may give one side of a breaking story, Wikipedia often provides a holistic overview of all the news sources available on a given topic.

Wikipedia already has clear policies on transparency, verifiability, and reliable sources. What it doesn’t have is the knowledge that universities have behind closed doors; often separated into silos or in pay-walled repositories. What it doesn’t have is enough willing contributors to meet the demands of the 1.5 billion unique devices that access it each month in ensuring its coverage of the ever-expanding knowledge is kept as accurate, up-to-date & representative of the sum of all knowledge as possible.

This is where you come in.

Conclusion

“It’s up to other people to decide whether they give it any credibility or not,” (Oakeshott in Viner, 2016)

The truth is out there. But it is up to us to challenge claims and to help verify them. This is no easy task in the information age and it is prone to, sometimes very deliberate, obfuscation. Infoglut has become the new censorship; a way of controlling the seemingly uncontrollable. Fact-checking sites have sprung up in greater numbers but they depend on people seeking them out when convenience and cognitive ease have proven time and again to be the drivers for the virtual generation.

We know that Wikipedia is the largest and most popular reference work on the internet. We know that it is transparent and built on verifiability and neutral point of view. We know that it has been combating fake news for years. So if the virtual generation are not armed with the information literacy education to enable them to critically evaluate the sources they encounter and the nature of the algorithms that mediate their interactions with the world, how then are they to make the informed decisions necessary to play their part as responsible online citizens?

It is the response of our governments and our Higher Education institutions to this last question that is the worry.

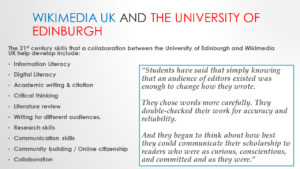

Postscript – Wikimedia at the University of Edinburgh

As the Wikimedia residency at the University of Edinburgh moves further into its second year we are looking to build on the success of the first year and work with other course leaders and students both inside and outside the curriculum. Starting small has proven to be a successful methodology but bold approaches like the University of British Columbia’s WikiProject Murder, Madness & Mayhem can also prove extremely successful. Indeed, bespoke solutions can often be found to individual requirements.

Time and motivation are the two most frequent cited barriers to uptake. These are undoubted challenges to academics, students & support staff but the experience of this year is that the merits of engagement & an understanding of how Wikipedia assignments & edit-a-thons operate overcome any such concerns in practice. Once understood, Wikipedia can be a powerful tool in an educator’s arsenal. Engagement from course leaders, information professionals and support from the institution itself go a long way to realising that the time & motivation is well-placed.

For educators, engaging with Wikipedia:

- meets the information literacy & digital literacy needs of our students.

- enhances learning & teaching in the curriculum

- helps develop & share knowledge in their subject discipline

- raises the visibility & impact of research in their particular field.

In this way, practitioners can swap out existing components of their practice in favour of Wikimedia learning activities which develop:

- Critical information literacy skills

- Digital literacy

- Academic writing & referencing

- Critical thinking

- Literature review

- Writing for different audiences

- Research skills

- Community building

- Online citizenship

- Collaboration.

This all begins with engaging in the conversation.

Wikipedia turned 16 on January 15th 2017. It has long been the elephant in the room in education circles but it is time to articulate that Wikipedia does indeed belong in education and that it plays an important role in our understanding & disseminating of the world’s knowledge. With Oxford University now also hosting their own Wikimedian in Residence on a university-wide remit, it is time also to articulate that this conversation is not going away. Far from it, the information & digital literacy needs of our students and staff will only intensify. Higher Education institutions must need formulate a response. The best thing we can do as educators & information professionals is to be vigilant and to be vocal; articulating both our vision for Open Knowledge & the pressing need for engagement in skills development as a core part of the university’s mission and give our senior managers something they can say ‘Yes’ to.

If you would like to find out more then feel free to contact me at ewan.mcandrew@ed.ac.uk

- Want to become a Wikipedia editor?

- Want to become a Wikipedia trainer?

- Want to run a Wikipedia course assignment?

- Want to contribute images to Wikimedia Commons?

- Want to contribute your research to Wikipedia?

- Want to contribute your research data to Wikidata?

References

Abram, S. (2016). Political literacy can be learned! Internet@Schools, 23(4), 8-10. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1825888133?accountid=10673

Alcantara, Chris (2016).“Wikipedia editors are essentially writing the election guide millions of voters will read”. Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Ashok, India (2016-11-18). “UK passes Investigatory Powers Bill that gives government sweeping powers to spy”. International Business Times UK. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

Bates, ME 2016, ‘Embracing the Filter Bubble’, Online Searcher, 40, 5, p. 72, Computers & Applied Sciences Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 10 December 2016.

Blumenthal, Helaine (2016).“How Wikipedia is unlocking scientific knowledge”. Wiki Education Foundation. 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Bode, Leticia (2016-07-01). “Pruning the news feed: Unfriending and unfollowing political content on social media”. Research & Politics. 3 (3): 2053168016661873. doi:10.1177/2053168016661873. ISSN 2053-1680.

Bojesen, Emile (2016-02-22). “Inventing the Educational Subject in the ‘Information Age’”. Studies in Philosophy and Education. 35 (3): 267–278. doi:10.1007/s11217-016-9519-2. ISSN 0039-3746.

Boyd, Danah (2017-01-05). “Did Media Literacy Backfire?”. Data & Society: Points. Retrieved 2017-02-01.

Broeders, Dennis (2016-04-14). “The Secret in the Information Society”. Philosophy & Technology. 29 (3): 293–305. doi:10.1007/s13347-016-0217-3. ISSN 2210-5433.

Burton, Jim (2008-05-02). “UK Public Libraries and Social Networking Services”. Library Hi Tech News. 25 (4): 5–7. doi:10.1108/07419050810890602. ISSN 0741-9058.

Cadwalladr, Carole (2016-12-11). “Google is not ‘just’ a platform. It frames, shapes and distorts how we see the world”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

Carlo, Silkie (2016-11-19). “The Government just passed the most extreme surveillance law in history – say goodbye to your privacy”. The Independent. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

Chaudhry, Peggy E. “The looming shadow of illicit trade on the internet”. Business Horizons. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2016.09.002.

Clarke, C. (2016). Advertising in the post-truth world. Campaign, Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1830868225?accountid=10673

Cohen, J. E. (2016). The regulatory state in the information age. Theoretical Inquiries in Law, 17(2), 369-414.

Cover, Rob (2016-01-01). Digital Identities. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 1–27. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-420083-8.00001-8. ISBN 9780124200838.

Davis, Lianna (2016-11-21). “Why Wiki Ed’s work combats fake news — and how you can help”. Wiki Education Foundation. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Derrick, J. (2016, Sep 26). Google is ‘the only potential acquirer’ of Twitter as social media boom nears end. Benzinga Newswires Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1823907139?accountid=10673

DeVito, Michael A. (2016-05-12). “From Editors to Algorithms”. Digital Journalism. 0 (0): 1–21. doi:10.1080/21670811.2016.1178592. ISSN 2167-0811.

Dewey, Caitlin (2016-05-11). “You probably haven’t even noticed Google’s sketchy quest to control the world’s knowledge”. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Dewey, Caitlin (2015-03-02). “Google has developed a technology to tell whether ‘facts’ on the Internet are true”. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Duggan, W. (2016, Jul 29). Where social media fails: ‘echo chambers’ versus open information source. Benzinga Newswires Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1807612858?accountid=10673

Eilperin, Juliet (11 December 2016). “Trump says ‘nobody really knows’ if climate change is real”. Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

Evans, Sandra K. (2016-04-01). “Staying Ahead of the Digital Tsunami: The Contributions of an Organizational Communication Approach to Journalism in the Information Age”. Journal of Communication. 66 (2): 280–298. doi:10.1111/jcom.12217. ISSN 1460-2466.

Facts and Facebook. (2016, Nov 14). Mint Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1838637822?accountid=10673

Flaxman, Seth; Goel, Sharad; Rao, Justin M. (2016-01-01). “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption”. Public Opinion Quarterly. 80 (S1): 298–320. doi:10.1093/poq/nfw006. ISSN 0033-362X.

Fu, J. Sophia (2016-04-01). “Leveraging Social Network Analysis for Research on Journalism in the Information Age”. Journal of Communication. 66 (2): 299–313. doi:10.1111/jcom.12212. ISSN 1460-2466.

Graham, Mark; Straumann, Ralph K.; Hogan, Bernie (2015-11-02). “Digital Divisions of Labor and Informational Magnetism: Mapping Participation in Wikipedia”. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 105 (6): 1158–1178. doi:10.1080/00045608.2015.1072791. ISSN 0004-5608.

Grathwohl, Casper (2011-01-07). “Wikipedia Comes of Age”. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 2017-02-20.

Guo, Jeff (2016).“Wikipedia is fixing one of the Internet’s biggest flaws”. Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Hahn, Elisabeth; Reuter, Martin; Spinath, Frank M.; Montag, Christian. “Internet addiction and its facets: The role of genetics and the relation to self-directedness”. Addictive Behaviors. 65: 137–146. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.018.

Heaberlin, Bradi; DeDeo, Simon (2016-04-20). “The Evolution of Wikipedia’s Norm Network”. Future Internet. 8 (2): 14. doi:10.3390/fi8020014.

Helberger, Natali; Kleinen-von Königslöw, Katharina; van der Noll, Rob (2015-08-25). “Regulating the new information intermediaries as gatekeepers of information diversity”. info. 17 (6): 50–71. doi:10.1108/info-05-2015-0034. ISSN 1463-6697.

Hillis, Ken; Petit, Michael; Jarrett, Kylie (2012). Google and the Culture of Search. Routledge. ISBN9781136933066.

Hinojo, Alex (2015-11-25). “Wikidata: The New Rosetta Stone | CCCB LAB”. CCCB LAB. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

Holone, Harald (2016-12-10). “The filter bubble and its effect on online personal health information”. Croatian Medical Journal. 57 (3): 298–301. doi:10.3325/cmj.2016.57.298. ISSN 0353-9504. PMC 4937233. PMID 27374832.

The information age. (1995). The Futurist, 29(6), 2. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/218589900?accountid=10673

Jütte, Bernd Justin (2016-03-01). “Coexisting digital exploitation for creative content and the private use exception”. International Journal of Law and Information Technology. 24 (1): 1–21. doi:10.1093/ijlit/eav020. ISSN 0967-0769.

Kim, Jinyoung; Gambino, Andrew (2016-12-01). “Do we trust the crowd or information system? Effects of personalization and bandwagon cues on users’ attitudes and behavioral intentions toward a restaurant recommendation website”. Computers in Human Behavior. 65: 369–379. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.038.

Knowledge, HBS Working. “Wikipedia Or Encyclopædia Britannica: Which Has More Bias?”. Forbes. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Korjus, Kaspar. “Governments must embrace the Information Age or risk becoming obsolete”. TechCrunch. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Landauer, Carl (2016-12-01). “From Moore’s Law to More’s Utopia: The Candy Crushing of Internet Law”. Leiden Journal of International Law. 29 (4): 1125–1146. doi:10.1017/S0922156516000546. ISSN 0922-1565.

Mathews, Jay (2015-09-24). “Is Hillary Clinton getting taller? Or is the Internet getting dumber?”. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Mims, C. (2016, May 16). WSJ.D technology: Assessing fears of facebook bias. Wall Street Journal Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1789005845?accountid=10673

Mittelstadt, Brent Daniel; Floridi, Luciano (2015-05-23). “The Ethics of Big Data: Current and Foreseeable Issues in Biomedical Contexts”. Science and Engineering Ethics. 22 (2): 303–341. doi:10.1007/s11948-015-9652-2. ISSN 1353-3452.

Naughton, John (2016-12-11). “Digital natives can handle the truth. Trouble is, they can’t find it”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

Nolin, Jan; Olson, Nasrine (2016-03-24). “The Internet of Things and convenience”. Internet Research. 26 (2): 360–376. doi:10.1108/IntR-03-2014-0082. ISSN 1066-2243.

Proserpio, L, & Gioia, D 2007, ‘Teaching the Virtual Generation’, Academy Of Management Learning & Education, 6, 1, pp. 69-80, Business Source Alumni Edition, EBSCOhost, viewed 10 December 2016.

Rader, Emilee (2017-02-01). “Examining user surprise as a symptom of algorithmic filtering”. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 98: 72–88. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.10.005.

Roach, S 1999, ‘Bubble Net’, Electric Perspectives, 24, 5, p. 82, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 10 December 2016.

Interfax (2016). Putin calls for countering of monopoly of Western media in world. Interfax: Russia & CIS Presidential Bulletin Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1800735002?accountid=10673

Seetharaman, D. (2016). Mark Zuckerberg continues to defend Facebook against criticism it may have swayed election; CEO says social media site’s role isn’t to be ‘arbiters of truth’. Wall Street Journal (Online) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1838714171?accountid=10673

Selinger, Evan C 2016, ‘Why does our privacy really matter?’, Christian Science Monitor, 22 April, Academic Search Premier, EBSCOhost, viewed 10 December 2016.

Sentance, Rebecca (2016). “Everything you need to know about Wikimedia’s ‘Knowledge Engine’ so far | Search Engine Watch”. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Smith, L.N. (2016). ‘School libraries, political information and information literacy provision: findings from a Scottish study’ Journal of Information Literacy, vol 10, no. 2, pp.3-25.DOI:10.11645/10.2.2097

Sinclair, Stephen; Bramley, Glen (2011-01-01). “Beyond Virtual Inclusion – Communications Inclusion and Digital Divisions”. Social Policy and Society. 10 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1017/S1474746410000345. ISSN 1475-3073.

Soma, Katrine; Onwezen, Marleen C; Salverda, Irini E; van Dam, Rosalie I (2016-02-01). “Roles of citizens in environmental governance in the Information Age — four theoretical perspectives”. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability governance and transformation 2016: Informational governance and environmental sustainability. 18: 122–130. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2015.12.009

Stephens, W (2016). ‘Teach Internet Research Skills’, School Library Journal, 62, 6, pp. 15-16, Education Source, EBSCOhost, viewed 10 December 2016.

Tambini, Damian; Labo, Sharif (2016-06-13). “Digital intermediaries in the UK: implications for news plurality”. info. 18 (4): 33–58. doi:10.1108/info-12-2015-0056. ISSN 1463-6697.

“A new kind of weather”. The Economist. 2016-03-26. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

Toobin, Jeffrey (29 September 2014). “Google and the Right to Be Forgotten”. The New Yorker. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

Tuffley, D, & Antonio, A 2016, ‘Ethics in the Information Age’, AQ: Australian Quarterly, 87, 1, pp. 19-40, Political Science Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 10 December 2016.

Upworthy celebrates power of empathy with event in NYC and release of new research study. (2016, Nov 15). PR Newswire Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1839078078?accountid=10673

Usher-Layser, N (2016). ‘Newsfeed: Facebook, Filtering and News Consumption. (cover story)’, Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 96, 3, pp. 18-21, Education Source, EBSCOhost, viewed 10 December 2016.

van Dijck, Jose. Culture of ConnectivityA Critical History of Social Media – Oxford Scholarship. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199970773.001.0001.

Velocci, A. L. (2000). Extent of internet’s value remains open to debate. Aviation Week & Space Technology, 153(20), 86. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/206085681?accountid=10673

Viner, Katherine (2016-07-12). “How technology disrupted the truth”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2016-12-11.

Wadhera, Mike. “The Information Age is over; welcome to the Experience Age”. TechCrunch. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

Weichert, Stephan (2016-01-01). “From Swarm Intelligence to Swarm Malice: An Appeal”. Social Media + Society. 2 (1): 2056305116640560. doi:10.1177/2056305116640560. ISSN 2056-3051.

Winkler, R. (2016). Business news: Big Silicon Valley voice cuts himself off — Marc Andreessen takes ‘Twitter break’ to the bewilderment of other techies.Wall Street Journal Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.is.ed.ac.uk/docview/1824805569?accountid=10673

White, Andrew (2016-12-01). “Manuel Castells’s trilogy the information age: economy, society, and culture”. Information, Communication & Society. 19 (12): 1673–1678. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1151066. ISSN 1369-118X.

Wine, Lois D. (2016-03-28). “School Librarians as Technology Leaders: An Evolution in Practice”. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science. doi:10.12783/issn.2328-2967/57/2/12. ISSN 2328-2967.

Yes, I’d lie to you; The post-truth world. 2016. The Economist, 420(9006), pp. 20.

Zekos, G. I. (2016). Intellectual Property Rights: A

Legal and Economic Investigation. IUP Journal Of Knowledge Management, 14(3), 28-71.

Figure 1 Bodies of Evidence (The Economist, 2016)

Figure 1 Bodies of Evidence (The Economist, 2016)

A bit of light reading on information retrieval – Own work, CC-BY-SA.

A bit of light reading on information retrieval – Own work, CC-BY-SA.